A Nuanced Perspective on Invasive Species

Here at PCEC, we wanted to take a moment to celebrate National Native American Heritage Month. We wish to acknowledge and amplify the vital role of Indigenous knowledge in this landscape, a body of wisdom that spans far beyond timelines we can easily fathom. There are more than 49 tribal nations associated with the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem with a history spanning at least 12,600 years.

In this spirit, I’d like to explore a nuanced perspective on the complex issue of invasive and native plant species, and the practice of deep ecology.

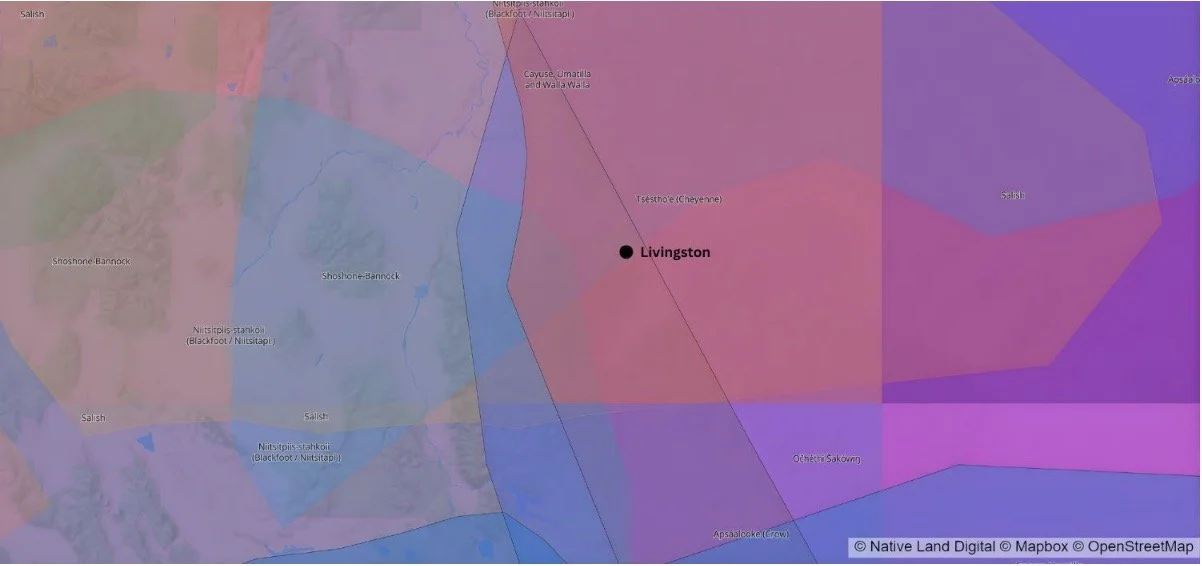

The Native Land Digital map (native-land.ca), an educational resource designed to decolonize modern geographical perspectives.

The restoration of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) across the West and here in Montana begins with the recognition of oral histories, deep connections, and relational observations forged over thousands of years and countless generations, which are particularly relevant as it relates to land stewardship. The integration of diverse forms of knowledge is increasingly recognized as a critical feature for maintaining and building social-ecological system resilience.

Please continue reading to discover a different way of observing the land, and learn more about the recent TEK research of Dr. Jennifer Grenz, a renowned Nlaka'pamux scholar, and Rose Bear Don't Walk, a Salish Kootenai scholar, on invasive species and Montana ethnobotany.

By Dr. Jennifer Grenz

In our community, we often approach non-native invasive species with a focus on control and elimination. Park County is applauded around the state for being an active community in invasive species management and education. Comparatively, there are fewer resources and opportunities to learn about native plants and integrated habitat management.

My time “in the weeds” has shown me that to truly understand healthy connected landscapes, we need to look beyond single target species. The land requires us to practice deep, integrated observation and actions on the systems we live in and manage.

In late August, working in the grasslands just west of the Absaroka Beartooth Wilderness, I was mapping a dense patch of spotted knapweed (Centaurea stoebe) along a chronically disturbed stream edge—an area that will likely remain in a state of early successional (weedy) development due to continued flood disturbance.

Instead of just charting the boundaries and measuring species diversity, I recorded other ecological activity and noted the complexity. First, I noticed the riparian vegetation was not in a natural state due to stream channel alterations, leaving mostly knapweed taproots to stabilize the bank. Most of the flowerheads had been eaten off by grazing wildlife, reducing the overall seed load. Its remaining flowers were essential forage for native bumble bees that had no other flowering forbs to feed on due to the extreme high heat and low precipitation that summer. In addition, as I pulled a couple plants, I noticed the roots were stressed by Cyphocleonus achates biocontrol agent, a root-boring weevil.

Just a few feet away was an intact community of thriving native perennial grasses and forbs: prairie junegrass, rough fescue, fringe sage, bluebunch wheatgrass, sulphur buckwheat, and needle and thread grass. These observations—though often outside standard monitoring protocols—are precisely what lead us to richer questions, relational understandings, and the deep context necessary for effective management.

While continued disturbance means this site will not remain in balance indefinitely, the observations immediately suggest a path forward.

We can add integrated practices like targeted/prescribed grazing or hand clipping before seeding occurs, revegetate the riparian edge to a more natural state, or restore stream channel sinuosity and re-establish floodplain connectivity in upper reaches to increase water storage and mitigate downstream peak flows, and seed with locally sourced native late-blooming drought tolerant forbs to support pollinators.

This layered approach, built on other observations, will help this system become more complex, lead to resilience, and lessen the impact and spread of invasive species.

This need for deep, context-rich observation is where the work of modern ecology requires the integration of TEK. Decades of Western ecological research on larger landscape-level threats like Invasive Annual Grasses (IAGs), such as cheatgrass and crested wheatgrass, proves that singular, short-term management fails to address the true scale of the problem.

IAGs are a catastrophic threat because they push Western rangelands past a critical ecological threshold, fundamentally altering fire regimes and soil biogeochemistry in ways that conventional control cannot reverse. This threat directly impacts a high majority of Indigenous lands, cultural practices, and food sovereignty by displacing the native plants Indigenous communities have relied upon for millennia.

Ultimately, effective management must rely on multi-scalar, long-term perspectives. Traditional Ecological Knowledge, oral history and stories of relationships with the wild, complement an essential framework that offers the relational understanding necessary to restore the ecosystem processes that suppress IAGs and rebuild native plant resiliency.

A resilience view of knowledge integration and ecological health sees opportunity in complexity!

Integrating Knowledge Systems

Dr. Jennifer Grenz, a renowned Nlaka'pamux scholar, offers a powerful framework for rethinking our approach to invasive species management. Rather than viewing it as a choice between knowledge systems, she successfully integrates Indigenous knowledge with Western science to develop innovative solutions. Her inspiring research, conducted while at the University of British Columbia, has led to the development of alternative land management practices and restoration techniques.

Specifically, her research has focused on IAG species like Scotch broom and how traditional harvesting practices can be used as a targeted management tool, offering valuable insights into land-based relationships and species coexistence.

Her work underscores the principle that humans are an integral part of the ecological system.

This research lays the groundwork for a new framework of "land healing" based on Indigenous principles, offering a constructive alternative to current conventional approaches. As Dr. Grenz states in her webinar:

By incorporating Indigenous knowledge and practices, we can develop more effective and sustainable restoration strategies, moving toward ecological resilience for the future rather than solely aiming to restore a fixed past condition. This involves understanding the unique history and site-specific ecology of each area, challenging the notion of a fixed "natural" state, and considering the long-term temporal implications of our management actions.

Montana Ethnobotany

Closer to home in the Flathead Region of Montana, Rose Bear Don't Walk, a Salish Kootenai scholar, is conducting important work in the fields of food systems, native plants, and ethnobotany. Her research sheds light on the crucial role Indigenous knowledge plays in tackling modern-day issues by directly focusing on community wellbeing and tribal sovereignty. Her findings specifically aim to aid collective efforts to restore, revitalize, and preserve valuable tribal resources in areas of health, language, and culture. This work fundamentally emphasizes the need to create stronger relationships between plants, people, and community health within the sovereign confederation.

You can learn more about this work, conducted out of the University of Montana, in the paper, Recovering our Roots: The Importance of Salish Ethnobotanical Knowledge and Traditional Food Systems to Community Wellbeing on the Flathead Indian Reservation in Montana.

Building on this concept of integrating Indigenous knowledge into land management, Rose Bear Don't Walk actively fosters community education through the Salish Plant Society. This organization aims to enlighten the community on regional plant life’s medicinal and cultural significance. The deeper we understand and integrate these relationships, the greater the potential for healing, leading to healthier communities and more resilient landscapes.